The Coral Reef Arks continue to come to life

Vieques, Puerto Rico in December 2022

Vieques, Puerto Rico in December 2022

From May 2022 to August 2022, Hervet Randriamady, a Ph.D. student in Population Health Sciences at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), conducted qualitative assessments in 7 communities across the Bay of Ranobe to better understand the mental health challenges in the southwestern region of Madagascar. His overall hope is to evaluate the potential mental health impacts of climate change-driven food insecurity.

Hervet is co-advised by Dr. Christopher Golden (Department of Nutrition) and Dr. Karestan Koenen (Department of Epidemiology) during his Ph.D. program and works closely with Dr. Kimberly Hook and Rocky Stroud II from HSPH. In addition, the study is in collaboration with the Ministry of Public Health’s Mental Health Department, represented by Dr. Hanitra Randriatsara.

Hervet wants to understand how environmental and climate change affect anxiety and depression in the Ranobe Bay communities once the longitudinal research is implemented in 2023. The anxiety and depression measurement tools will be simultaneously administered with dietary intake and socioeconomic surveys every four months for three years. To choose the anxiety and depression measurement tools that are culturally appropriate for the Bay of Ranobe communities, the qualitative study conducted from May to August 2022 was crucial:

To identify significant mental health and psychosocial issues among adult people in the Bay of Ranobe.

To identify commonalities and differences in the experiences and needs of mental health problems in adults in the Bay of Ranobe.

To describe local conceptions of mental and psychosocial health and illness and define the terminology used to describe these experiences.

To describe critical elements of healthy functioning and resiliency in the local context and in the local language.

To understand the experience of mentally ill people and the process of seeking care (or not) both in formal government clinics and with traditional healers in the Bay of Ranobe area.

Hervet was supported by several local students: Romario (IHSM), Madeleine (Univesity of Toliara), and Aro Faliniariana (IHSM) to conduct research in the field.

The team conducted six focus groups and 32 free-listing exercises in the Ranobe area from both Vezo (fishing communities) and Masikoro (agriculturalist communities). The most frequent themes that cause anxiety are:

Worrying about providing food to their children.

Unsustainable livelihoods due to drought.

The scarcity of seafood products.

Thanks to Dr. Hanitra Randriatsara, Dr. Nivohanitra Razafindrasoa, Dr. Vola Nirina Andrianavalona, and Nadège Verson Volasoa from the Ministry of Public Health team, who conducted the focus groups.

I am happy to share an update of the work that the Human Health and Livelihoods team is doing. Our team consists of Chris Golden, Hervet Randriamady, Heather Kelahan, and me. And each of them will be sharing a news update soon.

Our team is seeking to answer these questions in the villages of the Bay of Ranobe, southwestern Madagascar: 1) What are people eating?; and 2) Is the seafood they are catching contributing meaningfully to their nutrition and livelihoods? We will assess people’s diets to answer the first question, and look to quantify human dietary diversity, the volume of seafood consumption, and the supply of micronutrients to the diet to assess adequacy of intake. To answer the second question, we will map the diet data and the seafood catch data to income surveys and human health indicators (e.g., stunting, wasting, hypertension, etc.). ” We will also attempt to assess how mariculture practices in the Bay contribute to food security and human health and well-being, as well as their potential interactions with natural and artificial reefs. Reaching these objectives would involve data collection through surveys.

Before the surveys can begin, I led a complete census of 12 villages in the Bay from March to June 2022. From this census, we counted 18,547 inhabitants distributed in 4,057 households and we were able to categorize 80 sources of income in all villages. The most common source of income is derived from the fishery. We have counted around 4,709 fishermen in the Bay with 75% male and 25% female. I also led the piloting of certain survey instruments, including household and individual questionnaires to collect information about the nutrition, health status, expenditure and income,... In parallel with the pilot I conducted participatory mapping of fishing areas in each village.

The team is now finalizing the questionnaires for the baseline survey and follow-up surveys that will be conducted in the communities of the Bay. This survey will allow us to capture a lot of information such as income, expenditure, health status, nutrition, coping strategies index, water and sanitation, etc. The follow up survey will be conducted simultaneously in sampled households in 12 villages around the Bay of Ranobe every 4 months during 3 years. My PhD research seeks to assess the socio-economic impact related to coral reef restoration, by integrating data across the other teams who are implementing the reef restoration, and collecting data on changes in fish diversity and abundance, and fish catch.

The subject of my thesis is the logical continuation of my Masters. I am a beneficiary of the ARTS scholarship of the IRD (Institut de la Recherche pour le Développement) to work on the biodiversity of reef fishes in southwestern Madagascar, in collaboration with the ARMSRestore project.

Marine resources exploited by small-scale fisheries play an important role in the food security of Malagasy coastal inhabitants, particularly the coastal communities of southwestern Madagascar. However, population growth and an increase in fishing pressure is leading to a decrease in the size of the fish landed and the overall biomass of the catch. The assessment of the status of the reef fisheries in southwestern Madagascar remains difficult due not only to the lack of regular monitoring data on landings, but also to the challenges of accurate species identifications.

My study aims to improve the knowledge of the exploited fish diversity with respect to those that are caught and the perceptions held by the fishermen. The collection of data on the study of the ichthyological diversity caught by small-scale fishermen in 12 villages of Ranobe Bay is being carried out from October 2021 to December 2022 within the framework of the monitoring of fish landings. My work is based on the collection of images and fin tips of the fish caught by the six main gears used in this area: gillnets, handline, speargun, beach seine, bottom seine and mosquito net trawl.

For the overall diversity in the areas exploited by the fishermen of Ranobe Bay, I will use the fin tips and environmental DNA metabarcoding. Water samples will be collected from the sites where the six artificial reefs will be constructed and also from nearby natural coral reefs, considered as control sites. Environmental DNA sampling will be done prior to the installation of the artificial reefs scheduled for December 2022 and one year after the artificial reef installation.

The study of exploited fish diversity and overall diversity will be combined with a study of fish diversity as perceived by fishermen. It will be based on a survey of the fishermen of the area.

The collection of images and fins of fish will be completed at the end this year. The next step in data collection will be the first environmental DNA sampling at the end of the year, to know the global ichthyological diversity before the installation of artificial reefs in Ranobe Bay.

The quantification of fisheries landings and fish biodiversity are among the ARMSRestore project objectives. The achievement of these objectives is attributed to the “Fisheries” team which is focused on the study of the small-scale reef fishery in Ranobe Bay, Southwest Madagascar.

The reef fishery of Ranobe Bay is the largest fished area in southwestern Madagascar (163 km²) with around 5,000 fishers recorded. In this region, small-scale fisheries are an important source of food and income for coastal populations. However, the sustainability of this activity is threatened by the degradation of coral reefs and population increases that result in a decrease in fish catch. In addition, there is the lack of appropriate management of the resources due to the lack of complete and reliable data on the state of the fishery. Thus, the major interest of this study is to provide complete and accurate baseline data to assess the effectiveness of artificial reefs in the enhancement of fisheries production, on the one hand, and to evaluate the overall exploitation level of this fishery based on fisheries indicators, on the other hand.

From October 2021 to December 2022, a fishery survey is being conducted in 12 fishing villages along Ranobe Bay. Data collection involves collaboration with 103 fishers per month using five main fishing gear types such as handlines, gillnets, spearguns, beach seines and mosquito net trawls. Data related to the fishing activity such as the fishing gear used per trip, the weight of the catches, the fishing grounds frequented, the effort deployed, and the income from the catches are collected within the participatory survey over 30 days. These fishers are also provided with GPS trackers in order to have precise information on the distribution of their fishing activity and catches. A landing survey is carried out once a month to determine the diversity of the fish caught at the family level as well as their size structure. To this survey is added biological sampling on sexual maturation of reef fishes. To date, over 500 fishing landings have been monitored. After implementation of artificial reefs in 2023, a survey every 3 months will be done in the area via experimental fishing.

These data are, on the one hand, crucial and relevant information for the reinforcement of resource management. On the other hand, they will serve as a basis to ensure the sustainability of the fishing activity while taking into account the local socio-economic context. Moreover, the project also has an original approach in evaluating the impact of artificial reefs on fisheries production, which is still poorly investigated and known in Madagascar.

Reef ecology is my focus and I am working towards a PhD as part of the ARMS Restore Project to restore the coral reef biodiversity in my country.

Similar to an underwater rainforest, coral reefs support 25% of all marine life in the world and over 500 million people worldwide for food and coastal protection. Healthy coral reefs support commercial and subsistence fisheries as well as jobs and businesses through tourism and recreation. Unfortunately, due to climate change and human activities, coral reefs around the world are threatened and coastal populations are becoming more vulnerable.

The Bay of Ranobe in southwest of Madagascar, where around 5000 fishermen are wholly depending on the marine environment for food, are becoming threatened by malnutrition due to declining fish catches, declining agriculture, and an increasing coastal population.

To address these issues, a new tool is being advanced by the Project Team: Autonomous Reef Monitoring Structures (ARMS) attached on the bottom to collect representatives of reef biodiversity. Deployed on healthy natural coral reefs, ARMS accumulated marine organisms that will be moved to artificial reefs after one year to jumpstart reef growth. Pivoting from the traditional PVC and stainless-steel design, we redesigned the ARMS using limestone because it is a natural substrate, is locally sourced, and the structures can be made locally through collaboration and employment of members of the community.

The effectiveness of limestone ARMS for collecting local reef biodiversity will be tested and quantified over the three years of the project, a large part of my PhD research. Six artificial reefs will be built inside the Bay of Ranobe and their biological impact will be measured and compared against natural coral reefs nearby. More specifically, the performance and benefits of seeding ARMS from healthy natural coral reefs onto three artificial reefs site will be compared to three artificial reefs without ARMS and three natural coral reef sites (without ARMS or an artificial reef).

Last year, 120 “seeding ARMS” were deployed on the most heathy reef in the Bay, where they will be left undisturbed for 12 months. Meanwhile, my team and I are conducting monthly surveys to study benthic succession on the ARMS plate in situ to describe the colonization and succession of benthic organisms on ARMS relative to the surrounding natural reef.

In January 2023, we plan to begin building the six artificial reefs inside the Bay of Ranobe. Ecological selection criteria have been developed by our team to help local communities identify locations that will yield the most benefit (e.g., fish biomass), based on my fieldwork and data collection to explore potential artificial reef sites in June 2022. Up next are community conversations to discuss the data and decide where to build the six 1-hectare artificial reefs.

Members of our team, including Dr. Gildas Todinanahary, Emma Gibbons, and José Randrianandrasana, deployed limestone ARMS in Ranobe Bay, Madagacsar in late 2022 and early 2023. These ARMS will cure or “seed” for one year, acquiring the biological components of a healthy reef, and then will be moved to artificial reefs to jumpstart community and ecosystem growth on the artificial structures. Photos by José Randrianandrasana and Thomas Lamy.

I had a wonderful time talking with early- and mid-career professionals from all over the globe who are interested in careers in marine science. There are some incredible opportunities out there for science and policy to work together for the oceans and people who depend on them. Thanks to The Explorers Club for hosting the events as part of Oceans Week.

Former Masters student Andrea Gamba published his thesis work in Frontiers in Marine Science—congratulations, Andrea! We used untargeted metabolomics to show that corals and their algae shift the fluidity of their lipid membranes forming cells in response to warmer waters. This means that even though they are partners, each has different physiologies and responses to stress, which may influence how well each can survive in warming seas.

The ARMS Restore project was featured in the Harvard School for Public Health magazine.

In mid-November our team of scientists from NIWC (Navy), San Diego State, and Harvard headed to Puerto Rico to install the first Coral Reef Arks in open water. The Arks are floating structures—an 8’ diameter geodesic sphere—designed to house coral reef ecosystems in the water column, where the flow rate is high, light is plentiful, and the organisms are away from land-based pollution. Our test, a proof-of-principle, is to install two floating Arks, each at 25 feet depth, in 55 feet of water offshore.

The trip was a success and we installed both Arks and both control sites—corals placed on the seafloor at 25 feet. Success required six scientists, seven professional SCUBA divers, nine support personnel, and three boats, truly a team effort! We will be returning to the Arks every three months to collect samples and will add ARMS—foot squared structures seeded with healthy reef organisms—at the six-month point. This work will continue for the next two years and is supported by ESTCP, an environmental research program of the Department of Defense.

Ark 1—an 8’ diameter geodesic sphere—loaded up and ready for deployment.

Ark 1 deployed, suspended at 25 feet.

A close-up of Ark 1 with hard corals attached to plates on top. We will measure the growth of these corals to determine the extent to which environmental conditions on the Arks benefit their health and growth.

Ark 1 from below, tended to by a diver

In 2020, our cross-Harvard team was awarded a grant from the Harvard Culture Lab and Innovation Fund. With these funds, we are teaching PIs how to implement Universal Design (UD), the design principle that built spaces can be made accessible for everyone (e.g., adjustable height workstations, closed captioning). Our team is producing a “how to” brochure for wide distribution, holding a training and discussion for interested PIs, and implementing UD in a handful of Harvard labs as pilots. We are also creating a database of accessibility features for the undergraduate sciences labs at Harvard (~200), removing barriers students encounter when seeking lab positions.

Our team hopes to open a dialogue among faculty who may not be aware of the barriers faced by students with disabilities. If labs can become more accessible, an accommodative culture can become the new norm.

Our grant team includes Maryam Borton (SEAS Environmental Health & Safety), Sofia Diaz-Rodriguez (Neuroscience Concentrator), Michelle Hermans (University Disability Resources), Logan McCarty (FAS Science Education), Tim Rogers (HMS/HSDM Disability Services), Gwen Volmar (Undergraduate Research and Fellowships).

How can STEM environments become more accessible to people with disabilities? I describe a few ways in a letter out today and hope others will recommend more via the @sciencemagazine NextGen Voices call.

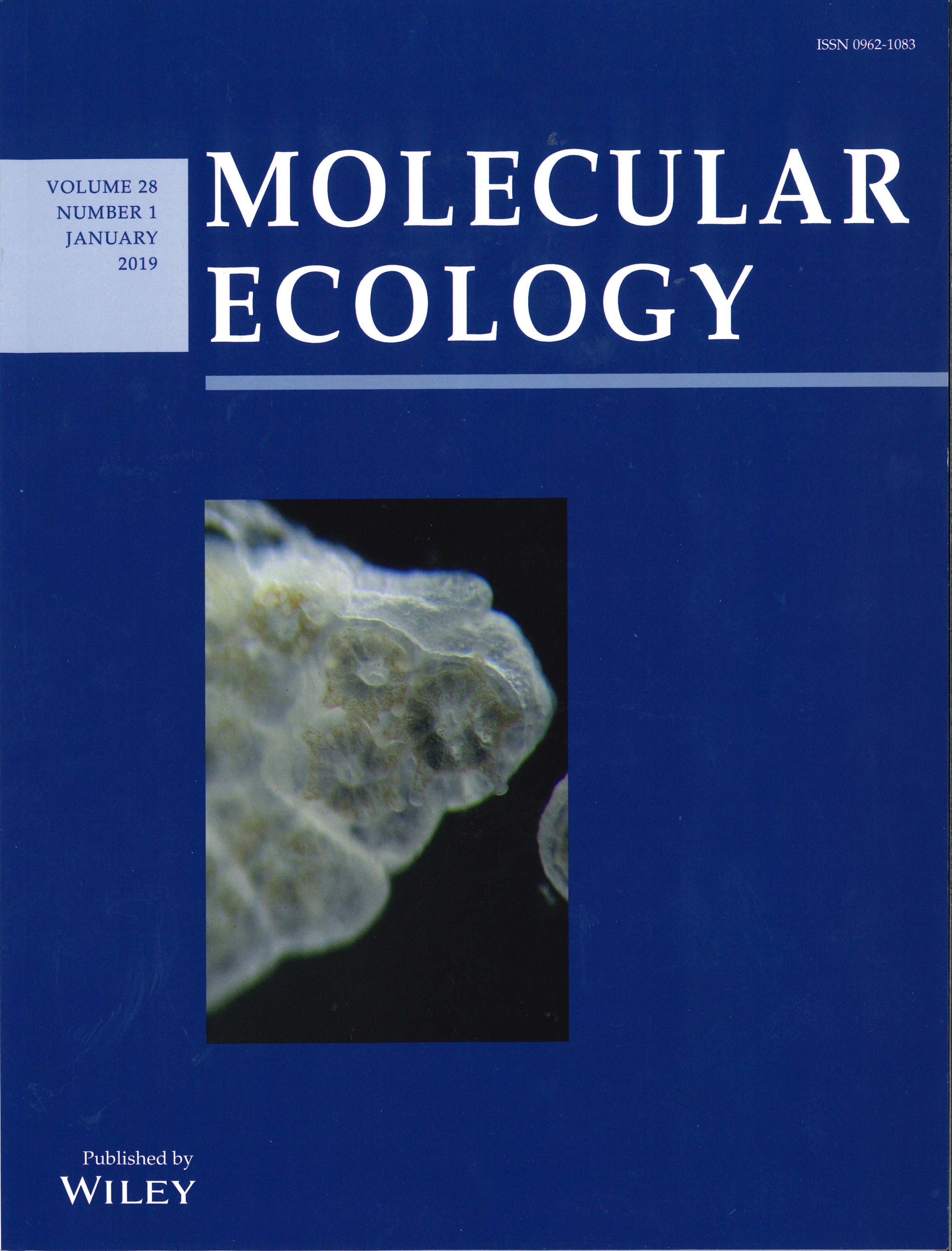

An exciting collaboration ended with coral babies making a journal cover (we’re honored)! This amazing photo, taken by Marhaver lab members at CARMABI Curaçao, shows baby star corals just after they have gone through metamorphosis. In this species, parents do not provide offspring with the algal symbionts they need to survive as adults. Instead, these baby corals must find them in their environment—or in the lab, as it may be. You can see the algal symbionts in the photo below as the tiny brown dots within the newly settled corals.

Paper summary: Even though it may seem like the sooner larvae can take up symbionts the better, we found that when swimming larvae take up symbionts it can actually throw off some of their behaviors and alter the ways they express genes and use energy (akin to the yolk). We concluded that these responses to taking up symbionts “early” is not beneficial to the larvae despite the fact that they benefit a great deal from these very same symbionts later in life. This means that while larvae can and will take up symbionts if they’re readily available, those that wait until later in life may survive better in the long run.

The citation is below and a pdf can be downloaded here.

A.C. Hartmann, K. L. Marhaver, A. Klueter, M. Lovci, C. J. Closek, E. Diaz, V. F. Chamberland, F. I. Archer, D. D. Deheyn, M. J. A. Vermeij, M. Medina (2019). Acquisition of obligate mutualist symbionts during the larval stage is not beneficial for a coral host. Molecular Ecology, 28, 141-155.

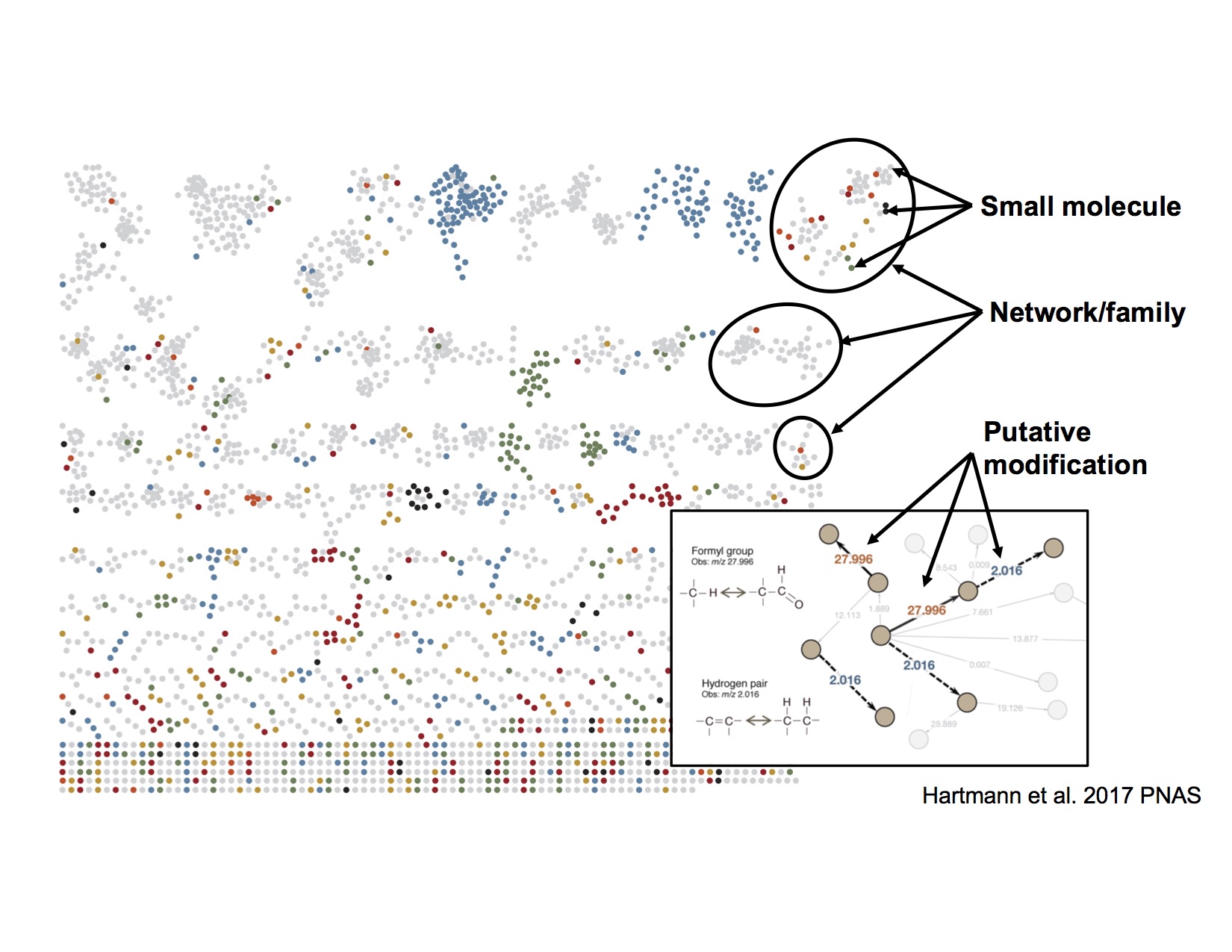

Animals produce certain molecules (think venoms) in order to fight for resources like space and food. In one of my projects, I am studying the mostly-unexplored diversity of molecules in coral reef organisms throughout the Coral Triangle, the most species-diverse spot in the ocean and maybe even the planet.

I’m trying to answer questions such as: Is small molecule diversity determined by the extent to which species are related? Or, is small molecule diversity determined by local communities and conditions? (local, it seems so far). I’m also interested in how much small molecule diversity is left to discover (lots and lots!). Quantifying this potential helps us understand why organisms win or lose on the reef and tells us that coral reef molecules have vast potential to benefit of humans (such as new medicines).

In May I gave talked about our preliminary findings at the World Conference on Marine Biodiversity in Montreal. I’m running follow-up analyses and will have more findings to share soon.

In the image below, all the grey circles are molecules found widely in the Coral Triangle, while the colored molecules are only found in one region. A molecular family is a group of molecules with similar structures and a modification relates to the chemistry that turns one molecule into another. You can read our paper on how we find modifications here.

Over an action-packed two days, my Harvard University Conservation Biology students visited five organizations to learn about marine conservation efforts in Maine. In particular, we got a close look at the interface between marine sustainability and aquaculture. Our stops included the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, Mook Sea Farm, Bigelow Marine Labs (including a delicious seaweed-focused dinner by Ocean's Balance), the Ocean Approved seaweed farm, Bangs Island Mussels, and the Friends of Casco Bay.

Getting a tour from Bill Mook at Mook Sea Farm, an oyster producer and one of the largest oyster seed hatcheries on the US east coast.

Checking out the Bangs Island floating mussel farm with Paul Dobbins of Ocean Approved seaweed.

Talking seaweed farming and getting out on Casco Bay with Paul Dobbins of Ocean Approved seaweed farm.

Interest in careers in environmental conservation is thriving at Harvard University and is led by the Harvard College Conservation Society. Every year the society organizes a Careers in Conservation Conference and I was honored to lead a workshop about career paths and work in the field of conservation biology. The free event is held every February and I strongly encourage anyone with interest in the field to attend.

In January I returned to the Maui Ocean Center, the site of one of my earliest attempts to catch coral babies (eggs and sperm). While there I gave a Sea Talk to interested members of the public on my research examining how the environment influences the early lives of corals. A video of my talk can be found below.